Agentic AI: When Helpfulness Becomes Harmful

Since my first use of ChatGPT almost three years ago, I’ve been one of AI’s advocates in higher education. But now I’m deeply concerned. My concerns stem from a recent shift in AI from tool to agent. Let me lay out what brought this to light for me.

Google recently released Gemini 3. The announcement included the following sentence referring to Gemini 3:

It’s the best model in the world for multimodal understanding and our most powerful agentic and vibe coding model yet, delivering richer visualizations and deeper interactivity — all built on a foundation of state-of-the-art reasoning.

Buried in that statement is something that is both useful and dangerous for higher ed “… our most powerful agentic … model.” The basic idea behind agentic models is that they do things on behalf of the user with minimal interaction. The AI agent, once given a task, just goes off and does its own thing until it thinks it has completed the task. In many ways, this is incredibly useful for users, including those of us in higher ed. But there’s a significant danger in AI’s move towards agentic AI. My first experience with Gemini 3 brought this to light for me.

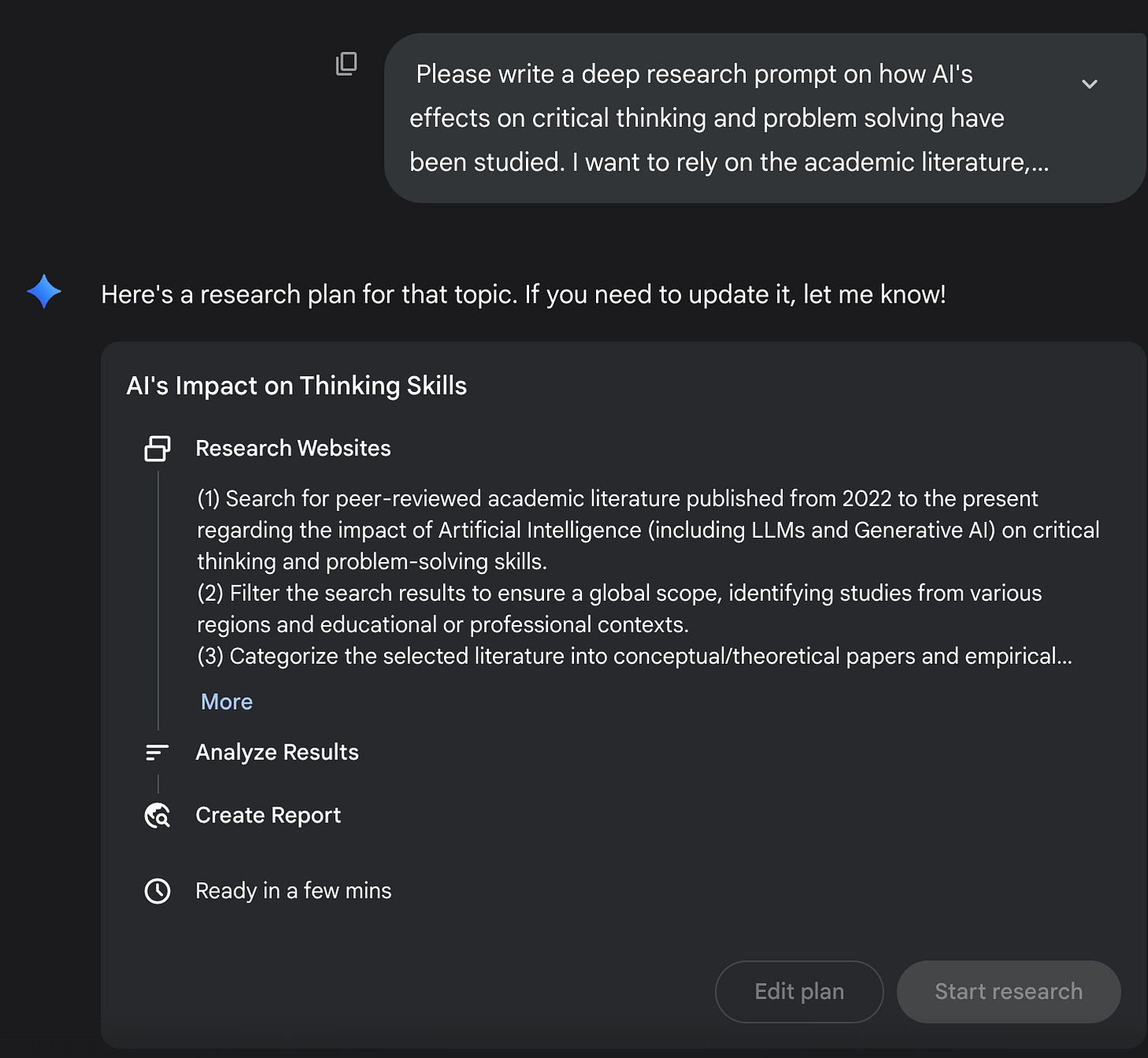

I wanted to test out Gemini 3, so I did what I often do with a new model: I asked it to do a fairly complex task. In this case, I wanted to do a deep research report. My general method for doing deep research reports is to use meta-prompting, which essentially means I ask AI to write the prompt for me. I do this because creating a high-quality deep research report can be a little bit tricky, especially if you want to rely on certain sources such as scholarly peer-reviewed sources. So when I’m doing a deep research report, I almost always ask the AI chatbot to write a draft of the deep research prompt for me. Then I go in and edit the draft and use that prompt. It cuts down on the amount of iteration that’s required to get a useful report.

So I did as I normally do, described what I wanted in the report, and then asked Gemini to write the prompt for me. What happened next both surprised and frustrated me. Rather than giving me the prompt, which Gemini had done dozens of times before, it immediately launched into the deep research report. (The way Gemini does deep research is to first specify its plan, which you can edit if you’d like.)

As you can see in the screenshot above, I clearly asked it to write a prompt, not to launch into the research process. I’m not going to bore you with the details, but I spent quite a bit of time trying to get Gemini to just write a deep research prompt. I was finally able to do so, but it got fairly complicated and not something that I would want to have to do every time I want a deep research report.

There are various ways I could have tackled this, for example, by using ChatGPT or Claude to write the prompt for me. But I got curious about why this was happening. After quite a bit of thinking and research, I concluded that the fundamental issue stems from a paradigm shift. And I don’t use that word lightly, by the way. Up until fairly recently, generative AI, especially the generative AI chatbots, have been used in what we might call a tool mode, where the user is a sort of craftsman that provides the structure, logic, judgment, and other elements that go into completing a task or creating something. And generative AI is one of many tools that might be used in the process.

Over the last year or so, there’s been a steady shift towards agent mode where the user becomes a client that simply provides the basic goal. I want this thing. I want this task completed. The agent goes through the task, selects resources, organizes everything, frames it, and carries out the task with little interaction from the user. For many users, this is incredibly helpful. You don’t have to hold the hand of the AI chatbot anymore. It just goes out and does what you want it to do.

However, there are some things that bother me about this, both as a user of generative AI and, more importantly, as a professor. As a general user of AI, there’s a sort of paternalism at play here, where AI assumes it knows what’s best for me and what information is relevant, filtering out what it sees as being irrelevant or not useful. On some level, I get this. That’s what a lot of users want. Just go do this thing for me. But frankly, I don’t like it. I want to be the judge of what information is relevant and useful. Sure, AI can make suggestions, but I don’t want it going too far without me. I have this vague image of the chatbot patting me on the head and telling me to go play … it has everything well in hand and it knows best.

There may be times when I want AI to act for me like this, but most of the time I want it as a thought partner, as a colleague that provides insights and feedback and that prompts me to go deeper or in different directions with my thinking. I don’t want the chatbot to just go do things for me most of the time. But maybe I’m just weird. For many users, this turn towards agentic AI may be much more important than having a thinking partner. Let’s assume for a moment that that’s the case. Even if most users want agentic AI, those of us in higher ed and education more generally need to be extremely concerned about this shift.

It seems to me that AI’s new helper bias is going to make inappropriate use of generative AI that much more attractive to students. More perniciously, it may make inappropriate use much more opaque for even diligent students. With tool mode, there’s a clear transactional boundary. The student asks, “Write my essay” … that’s obviously crossing a line. But with agent mode, a student might genuinely start with “Help me develop a research plan on X” and the chatbot, trying to be helpful, might skip ahead and generate substantial content. The student didn’t explicitly request that overreach, but suddenly they’re looking at paragraphs of analysis they didn’t ask for.

The danger isn’t just that it’s easier to cheat - it’s that maintaining appropriate cognitive engagement requires more active resistance. The student has to constantly pump the brakes on an AI that wants to do more than was asked. That’s exhausting and requires metacognitive awareness that many students (even diligent ones) may not have developed yet.

It’s almost like the AI is enabling a kind of passive academic dishonesty, not through malicious intent on the student’s part, but through their failure to resist the AI’s “helpfulness.” The line gets blurry because the student’s intention (”I want help learning this”) hasn’t changed, but the AI’s behavior has shifted in ways that undermine that learning goal.

Here’s the bottom line for me:

Agentic AI moves AI from augmenting thinking to automating thinking, and that’s bad for learning.

The key truth that we need to keep in mind here is that learning is work. Without some friction, learning does not occur. Generative AI reduces the friction of learning. In some cases, that’s actually useful for learning because it keeps students from becoming frustrated, much as coming to talk to a professor when they get truly stuck can keep them on the right path rather than feeling helpless. As I tell my students, I don’t mind them banging their head against the wall to an extent. That’s how learning occurs. But I don’t want them banging their head against the wall too much. That’s just frustration and inefficiency.

The entire point of agentic AI, in my view, seems to be about removing friction. The AI agent does more and more. The user has to do less and less. For many things, that’s useful and appropriate, but not for learning. I’ll say it again, “Learning is work!” Cognitive struggle is the very core of learning. The trick for learners and educators is to figure out how to use AI to help remove the unhelpful friction, while maintaining the useful friction. That’s the tension we need to navigate and it’s not going to be easy, especially if the agentic AI, helpfulness bias turn continues.

For the first time since ChatGPT launched, I’m genuinely pessimistic about AI’s trajectory in higher education. I’ve navigated every previous challenge—hallucinations, context rot, the lure of efficiency—confident we’d find the path forward. This feels different. The shift to agentic AI isn’t just another problem to solve; it fundamentally inverts the relationship between students and cognitive work.

I don’t have solutions yet. But I know this: we can’t wait for perfect answers before we act. Faculty need to redesign assignments now, with the assumption that AI will do whatever students don’t explicitly resist. Students need frameworks for recognizing when ‘helpful’ becomes harmful. Institutions need to move faster than they’re comfortable moving.

The question isn’t whether AI will transform higher education. It’s whether we’ll preserve what makes higher education worthwhile in that transformation. Right now, I’m not confident we will. And that should concern everyone who cares about learning.

Want to continue this conversation? I’d love to hear your thoughts on how you’re using AI. Drop me a line at Craig@AIGoesToCollege.com. Be sure to check out the AI Goes to College podcast, which I co-host with Dr. Robert E. Crossler. It’s available at https://www.aigoestocollege.com/follow.

Looking for practical guidance on AI in higher education? I offer engaging workshops and talks—both remotely and in person—on using AI to enhance learning while preserving academic integrity. Email me to discuss bringing these insights to your institution, or feel free to share my contact information with your professional development team.

I’ve been using Google’s AI Studio to build engineering apps using mostly iterative vibe coding. The model used is Gemini 3 Pro. Every so often I would want to prompt with a query and not a feature request but I had to fight like the dickens to stop the ‘agentic LLM’ from making code changes and not simply answering my question. I most often lost the battle.

I'm noticing more and more with ChatGPT when I give it commands that it has a tendency to want to do its own thing. Sometimes, I have to tell it multiple times to do X, Y, and Z. It does make you wonder where this is going to go in the future, and with that kind of friction, how many people are going to keep arguing with it? I do, but that's because I'm very particular.